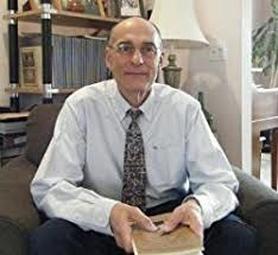

For this issue of Poets and Dreamers, I enjoyed the honor of speaking with poet and activist John Guzlowski, author of Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded. Having followed John’s works for years—his wisdom, his voice as a refugee, and his advocacy for the Displaced Persons of our nation—this interview has come to represent an important dialogue at a critical time for our world. I remember walking around the area along Milwaukee Avenue with my dad looking for an apartment to rent. My dad would see a “for rent” sign on a building, and we would walk up the stairs and knock on the door, but when the people realized we were Polish refugees they would say they couldn’t rent to us. People were afraid of us, I think. About John: Born in a refugee camp in Germany after World War II, John Guzlowski came to America with his family as a Displaced Person in 1951. His parents had been Polish slave laborers in Nazi Germany during the war. Growing up in the tough immigrant neighborhoods around Humboldt Park in Chicago, he met hardware store clerks with Auschwitz tattoos on their wrists, Polish cavalry officers who still mourned for their dead horses, and women who had walked from Siberia to Iran to escape the Russians. In much of his work, Guzlowski remembers and honors the experiences and ultimate strength of these voiceless survivors. Over a writing career that spans more than 40 years, John Guzlowski has amassed a significant body of published work in a wide range of genres: poetry, prose, literary criticism, reviews, fiction and nonfiction. His previously published books include Language of Mules (DP Press), Jezyk mulów i inne wiersze (Biblioteka Śląska), Lightning and Ashes (Steel Toe Books), Third Winter of War: Buchenwald (Finishing Line Press), Suitcase Charlie (Ravenswood), Echoes of Tattered Tongues (Aquila Polonica), and Little Schoolboys (Ravenswood). Echoes of Tattered Tongues, his recent memoir in poetry and prose, won the 2017 Ben Franklin Award for Poetry and the Eric Hoffer/Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking work of 2017. He has been honored by the Georgia State Commission on the Holocaust and the Central Virginia Holocaust Educators for his work on telling the story of slave laborers in Nazi Germany. In reviewing Guzlowski’s book Language of Mules, Nobel Laureate Czeslaw Milosz wrote, “Exceptional…even astonished me…reveals an enormous ability for grasping reality.” They didn’t call us Poles or Polish Americans. I never heard those words. What I did hear in the streets and in the schools was that we were Polacks, dumb Polacks and dirty Polacks. We were the people who nobody wanted to rent a room to or hire or help. We were the “wretched refuse” of somebody else’s shore, dumped now on the shore of Lake Michigan, and most people we came across in America wished we’d go back to where we came from.  Anne Tammel John, it is an honor to share this conversation. Can you tell us a bit about your history and how you (unexpectedly) became a critical voice for the displaced persons of our nation? John Guzlowski A lot of the writing that I do is about my parents and their story. They were both prisoners in German concentration camps and slave labor camps during the war. My dad spent four years in the camps, my mom spent two. I write about their experiences in my poems, have been since about 1978. I've done four books about them. Echoes of Tattered Tongues is a collection of all the poems and many of the prose pieces I've written about my parents. The publisher Aquila Polonica Press, concentrates on books about Poland and WWII. I sometimes feel that what I'm doing is continuing the talk my father started. He was a fellow who couldn't stop talking about what happened to him and my mom during the war. My mother would sometimes leave because he wouldn't stop. I inherited his mania for talking about the war. In fact, sometimes I wish I had listened more to him, so I could have more stories to write up into poems. What's odd for me about all of this writing about my parents is that I never planned to do it. It just sort of happened. But I guess that's the way that most writing works. AT: Which brings up an interesting question. Do we choose the stories and the people we write about? Or do they choose us? Sometimes we can’t forget a face or voice or something someone says. It becomes so vivid, the only way to truly process that in the end is to write about it. JG: Yes. What's strange to me is that really the only poetry I write that feels like real poetry, the real stuff poetry should be, is the poetry I write about my parents. I remember one time giving a reading of the poems about my parents, and a person in the audience asked me if I had some poems about myself, my life. It surprised me, his question. I never thought about reading anything about myself. My life, my impressions, didn't seem important enough to be written about. The real stuff was my parents and their lives and suffering. That was a long time, maybe thirty years or more. I've started writing more about myself but I think sometimes it's only because I've told my parents' stories, and they are no longer with me to tell me more. AT: When I read your stories—especially in the stories of surviving the streets of Chicago, your mother singlehandedly fighting off grown men with her grocery bags in hand—I feel like your parents are still alive. Having made it all the way to America, you had to then survive the tough neighborhood of refugees and survivors, and you all seemed to do so with invincible spirits. How? JG: I love to talk about Chicago and what it was like when we came to America. I recently wrote a poem about our first day in America, and it's a poem about miracles and magic, a world where every possibility is standing there in front of you with a loving face and open hands. That poem is in Echoes of Tattered Tongues, a book that gathers together all the old poems and a number of new ones. Yes, the constant miracle. My dad weighed 75 pounds when he was liberated, my mom weighed a 100. After the war they lived in a refugee camp for six years, and then they got a chance to come to America. They couldn't believe it. None of us could. I remember coming over on the troop ship and talking to my mom about all the things I expected to see. I was three years old, but I still remember my excitement and hers, talking about America. When we got here of course it was different. In our first apartment in Chicago, we lived with three other families, refugee families. We had no indoor plumbing, no hot water. I have a responsibility to my parents, to myself, and to every refugee and displaced person and outsider in this country, to write about being a refugee. And this is also finally a responsibility to America, to the world of Emerson and Whitman, to teach America that this is a land of diversity and it has to be allowed to be that. Always.  AT: On the topic of the displaced, like other refugees, did you feel embraced by America? Or did you feel like you were part of two cultures, not fully belonging to either? JG: I wish I could say we were embraced. But that’s not the way we felt. I remember walking around the area along Milwaukee Avenue with my dad looking for an apartment to rent. My dad would see a “for rent” sign on a building, and we would walk up the stairs and knock on the door, but when the people realized we were Polish refugees they would say they couldn’t rent to us. People were afraid of us, I think. They didn’t call us Poles or Polish Americans. I never heard those words. What I did hear in the streets and in the schools was that we were Polacks, dumb Polacks and dirty Polacks. We were the people who nobody wanted to rent a room to or hire or help. We were the “wretched refuse” of somebody else’s shore, dumped now on the shore of Lake Michigan, and most people we came across in America wished we’d go back to where we came from. I used to think that maybe it was just us, my mom and dad and my sister and me, something about us that set people against. But often when I do poetry readings and lectures about my family’s experiences, people come up to me afterward and share their stories, stories that are so similar to ours. Just a couple of days ago, I saw that TCM, a movie channel on cable, was doing a series of short non-fiction films about refugees in the US during and after World War II. These films were produced by the government. One of the films was The Cummington Story. This documentary told of a bus load of refugees that was brought to Cummington, Massachusetts during the war. What was so interesting to me was the response of the townspeople. They didn’t want these refugees, refugees from various countries and various faiths. The townspeople turned their backs on these people. It wasn’t until the minister of the town shamed the Americans there into treating the refugees as human beings that the townspeople began to open up to these refugees. For me the first years of the Trump administration have brought all of this back so forcefully. All of the talk of building walls to keep foreigners out, of sending people back to the countries they came from, of people being told they come from shit hole countries, of people from certain countries being blocked, of American citizens who were born here being threatened with deportation – all of this talk brings back the fear I had as a refugee kid back in the early 50s. And I think maybe for a lot of people in this country now this fear is greater than it ever was. AT: I recall a story you shared recently about visiting a dry cleaner. What happened that day, what did you carry in your heart as you walked away, not only for yourself but for all of America? JG: Something happened at Kroger that reminded me of something that happened years ago when we were living in Georgia. I went to our neighborhood dry cleaner with a batch of laundry that needed dry cleaning. The clerk took the order and asked me for my last name. I told her and she started laughing and said, "What kind of name is that?" I told her it was Polish and gathered my things together and left. AT: On the topic of the refugee and the displaced, one aspect I keep circling back to is that through your collection, Echoes, you give voice to those who cannot, for many reasons, speak for themselves. The topic of The Dreamers and Displaced is a critical one at this time in our history; we are a world in need of this dialog…we need poetic voices more than ever. How does your book apply to all refugees and displaced in America? JG: When I was growing up, I didn’t want anybody to know I was a refugee, a displaced person, a Polack. I wanted the world to see me as just another American kid. I ran from my refugee past. I didn’t talk about it, I didn’t write about it, I didn’t want any part of it. I remember when Language of Mules, my first book about my parents, came out. A friend of mine, my best friend who had known me since kindergarten, said he had no idea that I had this past, that my parents had been in concentration camps and that we came over as refugees. All of that changed when I started writing about my parents. This act gave me back my past and my parents. It taught me that I have to write about the thing that has hurt me most, has shaped me most. It taught me that I have a responsibility to my parents, to myself, and to every refugee and displaced person and outsider in this country, to write about being a refugee. And this is also finally a responsibility to America, to the world of Emerson and Whitman, to teach America that this is a land of diversity and it has to be allowed to be that. Always. AT: I remember not long after I’d lost my mother, you shared some words that gave me peace with saying goodbye to her. You simply said: “She is always there. Listen.” The topic of the poet as diviner or channel has come up several times. How much do these figures from the past speak to you through your work? JG: Oh, absolutely. The voices are what keep me writing. Poetry and writing in general for me is a way of connecting to that other world, the past, what was, history, memory. When I write about my parents, I can hear their voices. When I read poems about my parents I hear their voices. The greatest complement I ever received about my poems about my parents came from my sister. She said, I can hear mother and father in your poems. Writing I think connects me with myself and connects me with others. My first poetry teacher was Paul Carroll, and he used to say that all poets and writers were brothers and sisters, and when we wrote we talked to each other, the live writers and the dead ones. AT: I do believe writing connects us with different time periods and cultures so that we can better understand what motivates and moves each of us. We need to connect as a human race, and these stories unite us. JG: My first novel (Road of Bones -- about two German lovers separated by the war in the last days of WWII) grew out of a poem about my mom. I was writing a sonnet about the day the German soldiers came to her house in the woods outside of Lvov, and I came to the end of the sonnet. There at the end, a German soldier stood busying open the door to my mom's house. I stopped at that last line and asked myself, "What happens next?" I knew of course what would happen next. My grandmother is killed, my aunt is killed, my baby cousin is killed, my mother is raped but escaped through a broken window. I knew all that but still asked myself what happens next. And at that point I wrote a description of a German soldier pushing his way into the room. And I thought that I would be telling about what he did. But that's not what happened. The story of this soldier became something different. I assumed his point of view, saw the room as he saw, it was like my mom's room but different. I started listening to this soldier, the way I would listen to my father's stories as a child. The soldier led me into his world. A strange experience. We talked about voice earlier and listening to voices and recreating them for our poems. This was like that. Finally, what I discovered was that this soldier was one of the soldiers who was in the room with the soldiers who did the terrible things to my mom and her family, but he carried the burden of his guilt. The novel is about him working toward forgiveness, penance, salvation, redemption. It sounds like a Dostoevskian character, and in some ways the hero of this novel is. AT: We also write about what we fear. Not so much because we want to, but to continue on our paths as human beings, we must face our calling, explore these topics, and evolve. And as a culture, we must remain conscious... JG: I think in some way that fear connected me to my parents, taught me something about the fear they felt in the camps. There are still so many (survivors) stories that haven't been heard. I think that if have the chance, we need to listen and then write down those stories. One of the things I like about giving readings of poems about my parents is that often I meet people who have stories, who are survivors, and I love talking to them. They have seen something terrible in their lives and still go on, still live in joy and readiness. I remember one time talking to a woman after my reading. She had been sent to Siberia by the Soviets and escaped by walking to India. She came up to me smiling and said, "You talked about your mother spending a week in a boxcar. That's nothing. I spent two months in a boxcar." She said that and laughed. Like it was some kind of silly competition. It was wonderful to hear her story, hear her laugh. AT: On the topic of shifting between poetry and prose, can you work on both at the same time, or (like me) do you need to separate the two? JG: I think you're right about needing to separate the two. Prose for me requires so much more concentration. When I'm writing fiction, I need 3-4 hours at a time, to sit and think and create the world my character is moving through. And I need during the day and during the night to think about what's going on in the novel. When I'm writing prose, my mind is consciously working through problems like this. It’s not like that when I’m doing a poem. As a poet, I get taken by small objects, the color of the light, the sound of something just in the background, and I want to write it down. I guess there's a kind of freedom in poetry that you don't feel in prose. I remember one time showing a chapter from my novel Suitcase Charlie to a friend and having him ask, "Why do you spend so much time talking about the blueness of this telephone?" I was surprised. As a poet, I wondered why shouldn't I write about this blueness? As a novelist I said, you're absolutely right. AT: I watched a documentary about the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski, who did not want to use a lot of film; he spent hours getting a sugar cube to dissolve in coffee within the precise timing—in exactly four seconds, not three, and not five. The poet in me said: this is essential to the art! A novelist would say: give us the plot! But there is something magical that happens in a poem--it sounds like perfect music when it arrives. I like to believe this is our main job as poets, to remain true to that musical voice. JG: Yes, remaining true to that voice. There are muses and voices and we have to listen to them. When I'm writing a poem, I sit down and write something, put it aside, come back to it and write some more, put it aside, and return a week later to gather together all the pages and fragments of pages and start assembling. It's much more of an unconscious sort of process. I guess what I want to do as a poet/prose writer is to somewhere find a balance. Some of my favorite moments in my novel Suitcase Charlie take place when the detective is going through a suspect’s house, and he finds a complete edition of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica! It has nothing to do with the plot but suddenly I was describing it, and everything I ever thought or dreamed about that edition suddenly appeared on the page. I went on for pages and pages about this edition. Of course I had to cut out two pages of the description of the edition, but I kept one beautiful paragraph about the 1911 encyclopedia in! AT: On this topic of writing and how it transforms us, we have spoken a few times about the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, the father of transcendentalism, who I consider a literary father and guide to so many of us. Can you share your thoughts on transcendentalism? Do you feel you achieve transcendence in your life, and how? JG: Emerson. I love Emerson and Whitman, for me they are the great American writers. And what I love about them is their shared sense of Transcendence. Emerson has an image of himself as being a transparent eyeball! A wild image, but I think I get it. He wants to be open to experience, let it flow through him, touch every part of him, and touch every part of it. There's a lack of self-consciousness in this that I feel when the writing is really going well. I've opened myself up to experience and let that experience roll through me and onto the page. I've talked to musicians and artists, and they all experience something similar. I remember something Whitman said about breaking down the doors, and opening the windows. Writing and art do that for me... John's collection, Echoes of Tattered Tongues, is available on Amazon, as well as directly through the publisher, Aquila Polonica Press.

1 Comment

|

AuthorAnne Tammel Archives |

Poets and Dreamers, LLC

San Clemente, CA

So we travel on earth seeking the terrain of Poetry, walking through wilderness and empty landscape or visiting those ancient sites like Dholavira in far-western Gujarat, or Mykenai in the Greek Peloponnese, or the Arawak campsite on eastern Carriacou in the Grenadine Windward Isles, pursuing that authenticity of experience in a form of antique material reality...

These are places, strange and vague situations where death is manifold and thoroughly extant to the careful eye. There are women’s bangles made of shell to be picked up from the saline dust or small copper beads and thin chert blades, or tiny obsidian arrow-heads that can be unhidden and disclosed beneath those bloody grey walls about the Lion Gate, or beautiful indented potsherds and ceramic fragments at the waterline where the Atlantic rolls out its long blue visceral waves...

Kevin McGrath 🐚Yoga of Poetry

“Dare to live the life you have dreamed."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

What began as a circle of interactive teams and innovative salons evolved into a success-based network focused on culture transformation, team alignment, and entrepreneurial mindset. Poets and Dreamers guides executive leaders, professional teams, and businesses through developing and implementing innovative strategies, delivering consulting, coaching, and collaborative events that connect teams and leaders to arrive at the greatest levels of success. Poets and Dreamers Literary Circle and the Poets and Dreamers Journal exist as opportunities for artists to actualize their visions through collaboration and the circulation of literary and fine arts. Our literary and publishing services are focused on crafting, publishing, and circulating professional and literary works and fine arts. Our unique collection of products connect the world with poetry and unite the world through art.

"Remember...the entrance door to the sanctuary is inside you."

~ Rumi

|

Join the Poets and the Dreamers.

Our mailing list receives exclusive offers and announcements. |

Contact Us |